I like cemeteries, especially the old ones. They’re time machines, filled with artwork and stories. I’m as curious about the people who carved grave monuments as I am about those who lie beneath and around them. On a recent sunny Saturday, I got a chance to ride through Spring Forest Cemetery, off Mygatt Street in Binghamton. One stone read “Died at Age 70” with a death date of 1845. That meant she — it was the grave of a woman — was born in 1775, one year before the Declaration of Independence! How’s that for time travel?

What connects me to that old, old woman is the work of a nameless stone carver, a skilled artist/artisan, whose deep, sure strokes remain beautifully legible after 168 years. I wonder about that carver, whether he was poor or well-paid, whether he was respected as an artisan or considered just another guy with a hammer and chisel. Was he native born or an immigrant? And what did “immigrant” mean in 1845 Binghamton? Did he carve art for himself when he wasn’t working? What, I wonder, was his name and how is his death memorialized? And I wonder about the old woman under the headstone he made, what kind of life she lived, what it was like to live to age 70 in the early 1800s, when slavery was legal, there were no income taxes and tombstones were works of hand-carved artistry, probably for the well-to-do.

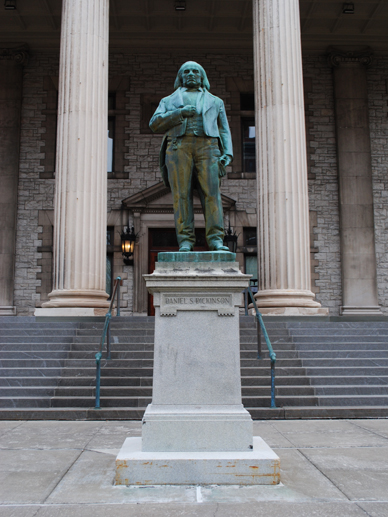

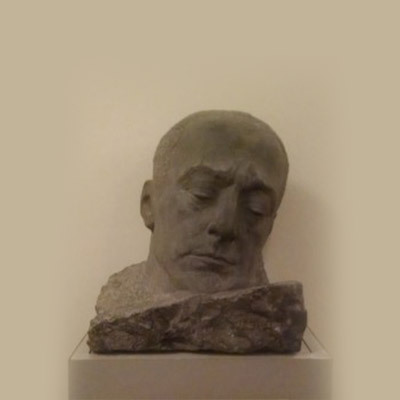

Over there, I notice the top of a large monument covered in gracefully folded stone drapery, frozen in motion and time. And over here, I see a couple of giant hunks of rough granite from which huge, diagonal crosses emerge, as though they’ve been waiting inside for the sculptor to free them, as Rodin imagined. And there stands a forest of plain and ornately carved obelisks, symbol of a masonic founding father, ancient Egypt, modern Istanbul. I like cemeteries, especially the old ones. They’re time machines filled with artwork and stories, fueling imagination.

— Sharon Ball