Reviewed by George Basler

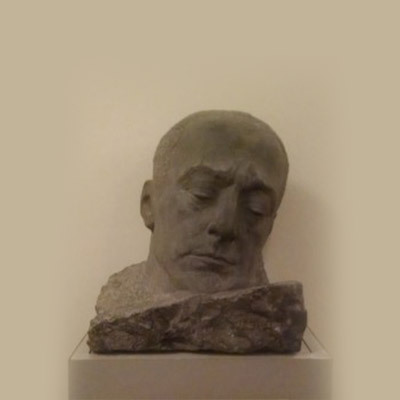

As the play Red opens, Mark Rothko is an aging artistic lion at the height of his powers and renown.

But he’s not a happy man. “We’re a smirking nation under the tyranny of the fine,” he sneers at one point before adding, “We are anything but fine.”

The peek into Rothko’s innate despair is one of the key plot points of Red, which opened this past weekend (April 14-17) at the Cider Mill Playhouse in Endicott. The intelligent, well-acted production asks questions about artistic integrity and whether art should disturb or comfort. It also probes the psyche of two emotionally wounded men who simultaneously desire and reject a father-son relationship.

The two-character drama, well-directed by Carol Hanscom, features Tom Kremer as Rothko and Ben Williamson as his new assistant, Ken, whom Rothko hires to do menial jobs around his studio. Both give first-rate performances and work effectively together.

The action takes place during 1958 and 1959 as Rothko, one of the giants of the Abstract Expressionist movement, works on a series of four murals for the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York City. The murals never made it into the restaurant, however, after Rothko withdrew them, feeling diners in a posh watering hole wouldn’t give them the attention they deserve.

The John Logan play received mixed reviews when it opened in London in 2009. Daily Telegraph critic Charles Spencer noted sarcastically: “Red will almost certainly become a snob hit among the chattering classes, who will then go on to patronize the kind of swanky restaurant Rothko despised and discuss the play over starters.”

But the Broadway production, which opened in 2010, received nearly unanimous raves and won the Tony Award for best play of the year.

No question the play is a challenging one. The Cider Mill production engages the mind more than the heart. Some may find it a bit pretentious as the two characters debate the nature of art and the nobility of pure art versus the alleged baseness of commercial work.

Still Red raises interesting and provocative questions about the artist’s role in society and the emotional price an artist pays for his, or her, insights. Moreover, the slow unveiling of the characters’ emotional layers is effectively done.

As played by Kremer, Rothko is opinionated, bullying and arrogant. But he’s also vulnerable as he fights despair and a sense of futility. New emerging artists are “out to murder me,” he shouts to his assistant (the real-life Rothko would ultimately commit suicide). Kremer effectively portrays both emotional extremes, keeping the audience off guard in the process.

At one point, for example, Kremer plays Rothko as being somewhat sympathetic while Ken recounts the murder of his two parents when he was seven. Thus, it’s particularly jarring when Rothko later hurls a hateful comment about the murder toward the young man. The insult drew gasps from the audience at the performance I attended.

Williamson is equally fine as the assistant. The character starts the play as a dewy-eyed innocent in awe of the great man who has hired him. Over the course of the play, however. he takes on a toughness and stands toe-to-toe with Rothko in exchanges that are dramatically fierce.

One especially fierce exchange happens when the assistant confronts Rothko over his destructive contempt for the art world, gallery owners and even people who actually buy his paintings. The pupil has turned on the master, so speak, prompting Rothko to enigmatically note, “this is the first time you ever existed.”

Don’t expect a big feel-good moment at the play’s end. The relationship between the two characters remains a complex and difficult one. It’s telling that the young painter never summons up the nerve to show Rothko his work. It’s equally telling that Rothko never asks to see it.

Red ends on an ambiguous note. Rothko simply dismisses the young artist, telling him to find his own path. The play hints that, in finding his own path, the young man may challenge Rothko’s work, and the great painter knows this. Rothko’s dismissal, therefore, can be seen as a noble act.

Logan underplays the moment. Like much of the play, it leaves audience members to make up their own minds.

The Cider Mill deserves credit for staging a play that is challenging and not a sure-fire audience pleaser. Kremer and Williamson create amazing portrayals of two men in an employer/employee relationship that comes to naught. The play will get you thinking.

IF YOU GO: Red will be performed 7:30 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays and 3 p.m. Sundays through May 1 at the Cider Mill Playhouse, 2 S. Nanticoke Ave., Endicott. Tickets are $28-$32; call 748-7363, or visit the box office from 12:30 to 6:30 p.m. Tuesdays and Wednesdays and 12:30 p.m. until curtain time on days of performance. You also can buy tickets online at www.cidermillplayhouse.org