Patchwork Houses

223 State St, Binghamton, NY 13901 223 State Street, Binghamton, NY, United StatesWe’ll make adorable patchwork houses by combining an assortment of [...]

We’ll make adorable patchwork houses by combining an assortment of [...]

Macrame is a string art that uses knotting to make [...]

CONTACT

Broome County Arts Council, Inc.

223 State St.

Binghamton, NY 13901

607.723.4620

Interested in becoming a member? Visit our membership page!

Individual BCAC Members enjoy the following benefits!

If you’re not a member of BCAC, you can still attend the BOA workshops for a small fee of $25.00 per session!

Scroll to the “Registration” section of this page for more information on registration for individual courses.

BCAC Members are eligible for up to 5 FREE individual business of art workshops in 2024

After 5 FREE workshops have been redeemed, BCAC only charges $15.00 per workshop for our members!

Please note only the following membership tiers are eligible to redeem the 5 free individual BOA workshops: College Student and Individual

Scroll to the “Registration” section of this page for more information on registration for individual courses.

test

Giant Coloring Page

Description: Art trail participants are invited to add to a collaborative coloring project with Spotgirl Design

Date/Time: Saturday, September 21st, 10AM-4PM

Location: The Discovery Center, 60 Morgan Road, Binghamton, NY. 13901

Stained Glass Tiffany-Style Reproduction Lampshades

Description: Michael will demonstrate the stained glass techniques used to create his Tiffany-Style reproduction lampshades.

Date/Time: Saturday, September 21st, 10AM-4PM and Sunday, September 22nd, 11AM-4PM

Location: Artfarm Giftshop, 200 Prentice Road, Binghamton, NY. 13901

Photographs provided by: the ACA Memorial Fund

Madeleine Cotts of BCK-IBI Group (Architect)

David Marsland (Project Manager)

Milon Townsend (Glass Artist)

ACA Memorial, 2013

Granite, casted glass, steel, and bronze

Corner of East Clinton & Front Street, Binghamton

Funded by the Families and Friends of Victims

The ACA Memorial was commissioned by the city of Binghamton to honor the memories of those lost in a tragic shooting that took place at the American Civic Association Building in Binghamton on April 3, 2009. On that day, a local resident armed with a gun entered the building and killed thirteen people before turning the gun on himself. The tragedy shocked the region and the country, given its national news coverage. It also traumatized the local immigrant community, which had long benefited from the language classes, social events, and other activities arranged by the ACA.

The memorial offers a vision of healing meant to honor the memories of those lost in the attack. Completed in 2012, the project was the result of collaboration between Madeleine Cotts of BCK Architects and Engineers and project manager David Marsland, whose wife was one of the thirteen victims. The pair envisioned a memorial that would convey the emotional trauma felt by the victims’ loved ones, capture the diversity of those victims’ backgrounds, and provide a quiet space for reflection.

The memorial is orientated around a broken column, alluding to the nineteenth century Victorian symbol – typically used to memorialize a life cut short. However, the memorial designers chose to add a translucent glass element rising from the column’s center in order to bring the attention to the present. All nine sides the column bear a word or phrase of peace or non-violence in each of the nine native languages of the victims.

Surrounding the column are thirteen sculptures of birds in flight, with wings outstretched, so as to capture the victims’ animated spirit. Milton Townsend, the glass artist hired to create these figurines, stated that these thirteen birds are meant to symbolize the thirteen victims of the shooting, each of whom passed on and flew from this world to a new one. The birds themselves are cast in glass and internally illuminated by LED lights. Each bird is carefully positioned atop a fifteen-foot steel stand, allowing the birds to appear as if soaring through the sky.

Since its completion in 2013, the ACA memorial has been the site of multiple services on the anniversaries of the attack. With its powerful imagery, the memorial illuminates the potential for a community to come together when clouded by the darkness of tragedy.

Researched by: Sam Davidowitz-Neu

Robert Aitken

(American, 1878 — 1949)

The Skirmisher, 1924

Bronze

Washington St. Bridge, along North Shore Drive

Gift of Thomas H. Barber Camp III United Spanish War Veterans and Broome County Board of Supervisors

Collection of the City of Binghamton, Broome County

The Skirmisher by Robert Aitken depicts a typical infantryman of the Spanish-American War (1898). The monument was proposed by Thomas H. Barber Camp III as a tribute to his fellow soldiers. Foster Disinger, a photographer based in Binghamton and an officer of the Broome County Historical Society, enlisted the help of his friend Robert Aitken, an internationally recognized artist, for the project. Aitken, who was also a veteran of the Spanish-American War, decided against the typical stationary soldier, which he felt to be lifeless, and instead gave the Skirmisher his distinctive and dynamic stance.

Skirmishers were men deployed in a military formation called the skirmish line, which required each soldier to charge into battle at a distance of eighteen to twenty feet from each other. This unusual formation aimed to counter the increasing accuracy of the rifles used in military conflict. Aitken’s Skirmisher balances on one leg atop a nine-foot cylindrical pedestal. The lively character closely resembles the men who charged forward into battle, aiming to capture the passion and dedication of the turn-of-the-century American soldier.

Binghamton residents were quite proud of the Skirmisher when he was dedicated in 1925, and aimed to make sure the sculpture, with its unique stance, remained unique to the city. According to Tom Cawley, writing for the Binghamton Press and Leader newspaper in 1967, residents of Brooklyn, New York, wanted a Skirmisher of their very own, but Aitken refused. The artist was determined to make the Broome County sculpture unique in every way. This local pride extended even into song: “Throw a kiss [to the Skirmisher], in memory of the men we still miss,” was a rhyme popular with children of the 1930s and 1940s and intended to keep the soldier’s memory alive.

Installed in 1924 and dedicated on July, 1925, during the annual parade of the United Spanish War Veterans Convention, Aitken’s sculpture has had an interesting post-installation history. It was initially part of a larger memorial plan: a Memorial Circle with a diameter of 260 feet at the intersection of Washington and Water Streets (later North Shore Drive) and purposely close to the World War Memorial Bridge of Broome County.

In 1958, the sculpture was moved north six feet and the circle was diminished to accommodate the increase of traffic from highway construction; the remaining circle was removed when the bridge was closed in 1969. During the sculpture’s most recent relocation to Confluence Park in 1996, a time capsule was discovered within its pedestal. The time capsule, a copper box, showed signs of damage. The items found within the capsule included newspapers from 1925, Spanish-American War badges, and a letter from 1958 explaining that the time capsule had been found within the pedestal during the relocation and replaced. It is believed that a new time capsule was placed within the base of the sculpture including its previous contents from 1925, 1958, and objects from its unearthing in 1996.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia

Yvonne R. Hobbs (1939 – )

Supporting Hands, c. 1986 (Dedicated 1988)

Bronze, bluestone, concrete

Binghamton General Hospital Outdoor Courtyard, Mitchell Avenue

Administered by United Health Services Foundation, Binghamton, NY

Supporting Hands was designed to symbolize donor support to the United Health Services Foundation. Located in the outdoor courtyard at Binghamton General Hospital, the sculpture serves as a permanent tribute to those who have demonstrated their generosity to United Health Services (UHS). Artist Yvonne Robare Hobbs was commissioned in June 25, 1985 to design the sculpture with the aim of representing the caring mission of UHS while recognizing donor support.

Supporting Hands is composed of a young, right hand supporting an older, work-worn hand. Seated upon these hands is a group of figures: a grandfather, child, and mother, indicative of the need for cross-generational interaction for mutual benefit. Further demonstrating the importance of those who venture before us, the artists used the lost wax process, which dates back to 4000 B.C.E., to achieve the detail present in this sculpture.

In undergoing this process, Hobbs first created maquettes which would be used to scale to the piece to the appropriate size. When the full scale model was finalized, it was sectioned off in order to make removable and reusable rubber molds. Once the molds were created, they were assembled using several layers of liquid wax. When the wax shells hardened, they were removed and then reassembled. The next steps consisted of draining the wax, pouring the molten metal, and making sure the system was properly vented. The burn out took place over a few days. Then the molten bronze was poured and allowed to cool down overnight. Finally, the surface patina of acrylic resin was added through the application of heat and chemicals.

Yvonne Robare Hobbs achieved a MFA in sculpture with honors from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as well as a BS in art education from SUNY Buffalo. A recipient of many awards, Hobbs exhibited her work in shows at prestigious galleries such as Cape May County Art League in New Jersey and the Studio School and Art Gallery in Binghamton. She also participated in the Imagination Celebration located in Binghamton. Hobbs’ work is influenced by her belief in the interrelationship of all elements in our environment. Using wax as her primary material, she is able to develop and refine her ideas to allow others to visualize the relationships apparent to her.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia

Peter Horstman, David Young, John Combs

Fountain & Sculpture, 1985

Concrete and steel

South Promenade, Susquehanna Urban Park

The fountain and sculpture is a part of the East Bank River Promenade that was constructed in 1985. When construction of the South Promenade began, the pre-existing fountain was restored, the surrounding area was redesigned and a sculptural element was added.

The fountain consisted of a circular pool with an underwater steel ring that released a cone shaped spray. Although the pool is no longer functional, you can see a concrete circle marking its absence. To the North of the circle is a curved concrete wall topped with a painted, circular, steel sculpture which mirrors the shape of the pool. Viewers standing above can look through the circle down toward the Chenango River, all the way to the confluence of the Chenango and the Susquehanna River.

In 2011 a group (Emily, Sam, and Susan Jablon, Kari Bayait, Anthony Santucci, and Chris Long) came together to bring the Promenade new life by incorporating mosaic tiles into the cement wall. With help from Kari Bayait, project originator, and the Southern Tier Celebrates organization (which closed in 2010), this project became a reality. With the glass tiles were donated by Susan Jablon Mosaics, this piece was the first mosaic put up in downtown Binghamton. The aim of this piece was to bring brightness and joy to the city. This artistic group wanted people to take pride in Binghamton.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia

Masao Kinoshita (American, 1925 – 2003)

I-Beam, 1972

Corten steel

Government Plaza

While at first glance the metal elements of Masao Kinoshita’s I-Beam might appear somewhat chaotic, further inspection reveals the carefulness of its ordering. Part of the difficulty in seeing the sculpture in full is due to its incomplete state. When it was installed in 1972, the sculpture included 26 water jets that are no longer functional today. These water jets together produced a veil of mist that enveloped the lower third of the sculpture, giving the illusion that its steel beam emerged from the water, as if from a cloud. The auditory and visual effects of the fountain were striking, especially at night when the composition of mist and beams was brilliantly lit. With the mist in mind, Kinoshita’s intention becomes clearer. As the artist put it in the brochure that accompanied its dedication in 1972, “the sculpture is meant to evoke a sense of emotional participation from a person’s eyes to his heart.”

Kinoshita was born in California but raised in Japan from infancy until the age of 15 when his family moved back to the United States. During World War II, Kinoshita was imprisoned in an internment camp for Japanese Americans in Arkansas. He was granted leave from the camp only when he became an interpreter for the United States Army. He later studied architecture and urban design at Cornell and Harvard Universities. In 1960s and ’70s Kinoshita became a highly successful landscape architect; perhaps most notably, he contributed designs for the plaza around Minoru Yamasaki’s original World Trade Center towers in Manhattan. He split his time between the United States and Japan, practicing painting along with landscape architecture and urban design.

It was while working for Sasaki, Dawson & Demay (now Sasaki Associates) that Kinoshita came to work in Binghamton. Kinoshita’s sculpture was a component of the firm’s design for Government Plaza downtown. Commissioned as a focal point for the plaza, I-Beam comprises three separate structures, each rising 40 feet above a granite base. Corten steel wide flanged beams were welded together to form fanlike sculptural pieces.

Researched by: Marissa Moroz

Louise Nevelson (American, 1899 – 1988),

Dawn’s Column, c. 1970 (Installed April 25, 1973)

Found objects, steel, concrete and pebbles

Government Plaza

Collection of the City of Binghamton

Dawn’s Column, completed by Louise Nevelson in 1970 and installed in Binghamton’s Government Plaza in 1973, reflects the artist’s commitment to abstraction, her background in constructed sculpture, and her interest in imbuing her art with a sense of spirituality. Nevelson was influenced by the early twentieth century avant-garde art movements of Cubism, Surrealism and Geometric Abstraction. Dawn’s Column bears marks of each of these influences.

Like a cubist collage, Dawn’s Column is as much about the spaces outside, within and around its forms, as it is about the geometric forms themselves. According to Nevelson’s biographer, Laurie Lisle, the artist once boasted that “Picasso had resolved the cube, Mondrian had flattened it, and that she had endowed it with poetry.” Dawn’s Column is a tribute to this poetic manipulation of Cubist form. Witness the play of light and shadow across matte metal, and notice how it changes as you circumambulate the base. Think of the sculpting of shadow as much as the sculpting of metal, and how these shadows constantly change throughout the day. The shadows themselves give the work an air of mystery, akin to Surrealism. Notice too how although Nevelson’s composition of found objects might appear random, the work’s monochromatic finish unifies it, a technique Nevelson used often.

The stark and remote concrete plaza in downtown Binghamton might seem like an out-of-place setting for a sculpture by a famous artist, but it actually aligns with Nevelson’s lifelong distrust of nature. The artist preferred the manmade to the organic. On her own property, she famously constructed a “garden” out of mechanical found objects in place of plants. The base of Dawn’s Column uses manmade materials to invoke the natural world. While the pedestal beneath most sculptures is solely functional, here the pedestal is dotted with thoughtfully placed white pebbles against a dark ground of concrete, creating a “pool” reflecting the starry night sky. In place of an actual reflection caused by nature, Nevelson offers her own version, supplanting even Mother Nature, displaying the ego she was famous for.

Despite starting a career in art during a time when women artists were largely ignored, Nevelson—a Jewish immigrant from a small Russian village—succeeded to such a degree that examples of her own brand of “geometry and magic” can now be found in major collections around the globe. Nevelson’s unique approach to sculpture forced the art world to consider her work alongside famous male contemporaries, like Alexander Calder and Henry Moore, and earned her the title “Grande Dame of Contemporary Sculpture.”

Researched by: Cindy Blackman

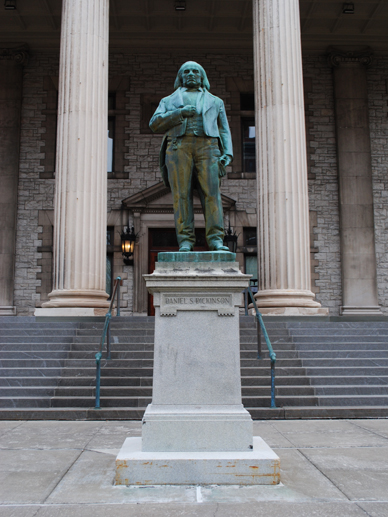

Allen George Newman (American, 1875 – 1940),

Daniel S. Dickinson, 1924

Bronze with granite base

Broome County Court House, 92 Court Street

Collection of the City of Binghamton

“I’d rather be right than be president,” said Daniel S. Dickinson (1800-1866) at the Democratic Convention of 1852 in Baltimore. Though he was never President of the United States, Dickinson was elected the first president of the village of Binghamton in 1834. He enjoyed a distinguished career as a politician and lawyer, including positions as New York State Senator, Lieutenant Governor of New York, and New York State Attorney General, all culminating in his election to the U.S. State Senate. Dickinson was regarded with great fondness for both his eloquence as a speaker and his persuasive skill. His graceful speeches frequently included both allusions to poetry and mythology, and he could denounce his opponents with scathing satire.

The project to erect a statue of Dickinson was initiated in 1915 by the Exempt Fireman’s Association of Binghamton, a group of distinguished volunteer firemen led by the organization’s secretary, Charles F. Tupper. Tupper enlisted the help of his friend, architect John Hemingway Duncan (1855-1929), who was New York-based but Binghamton-born, to find a sculptor who could portray Dickinson as accurately as possible. Duncan thought that Allen George Newman (1875-1940) would be the best man for the job. Newman was born in New York City and studied at the National Academy of Design with John Quincy Adams. Newman was well known at the time for his patriotic monuments, the most famous of which is The Hiker, a monument to honor American soldiers who fought in the Boxer Rebellion, the Spanish-American War, and the Filipino-American War. Copies of the famous Hiker can be found in parks and squares across the country. Erecting a statue of Dickinson was an expensive undertaking, and required cooperation from the entire community. Tupper was able to gather support from the local community for the project, and succeeded in amassing the funds to complete it, including a contribution of $1000 from George F. Johnson.

Newman’s statue of Dickinson was unveiled by Harold L. Harrington, Dickinson’s great-great grandson, on May 30th, 1924. A highly traditional monument, Newman’s sculpture portrays Dickinson as a grand, larger-than-life figure. The statesman holds a confident stance, his right hand tucked into his waistcoat and his left hand at his side holding papers. The hand in the waistcoat signifies boldness, tempered with modesty, a fitting gesture for a politician of Dickinson’s stature. Today, Dickinson stands outside of the Broome County Courthouse watching over the city where he began his career. Tupper envisioned the court house square as the location where Dickinson would forever stand and be memorialized; indeed, Tupper claimed, Binghamton had “the most beautiful public square in the entire state.”

Researched by: Alex Feim

Located within the courtyard of the 20 Hawley apartments, previously Marine Midland Plaza, stands a red-orange steel sculpture that captures pedestrians’ attention from beyond the gates. What you see here is the artist’s first large-scale commission. Arline Peartree attended SUNY Albany to receive her BA and MFA in sculpture. Art has always been her passion. Her art is inspired by post-1900s art like Persian art, Indian art, industrial design, fashion, dance, and music. It is art that “gives life poetry in visual forms.”

The artist was supplied with the architectural plans of the “Marine Midland Plaza” before it was built, in order to design her commission. She then made a model of the plaza and designed her artwork, evoking drama, energy, and uplifting emotions. Once her design was approved, she oversaw the welding of the steel in Stephentown, NY. It was then shipped in 3 pieces on a large truck and assembled in place with the help of a cherry picker crane and three men from within the plaza.

The support emerges from the earth at a 45 degree angle in order to support the horizontal beam twice its size. Crowning this prominent piece is a large open circle with square and cube forms. Originally the artwork was flanked by two still fountains that have since been morphed into the amenities of the apartments.

Since creating this piece, the artist has developed more geometric and lyrical sculptures, as well as paintings on metal, water colors, and acrylics. Her work is never realistic and is concerned with abstraction, emotional mood, and sincerity of materials. You can find her entire body of work on her website.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia

Photos by Jillian Proscia

Ed Wilson (African American, 1925 – 1996),

Seven Seals of Silence, 1969

Granite, bronze

Kennedy Park, Intersection of Chenango & Henry Street

Ed Wilson, born in 1925 in Baltimore, Maryland, was trained in painting and sculpture at the University of Iowa. In 1953, he received his master’s degree in sculpture. He eventually became a Professor at North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University) in Durham; later, he accepted the invitation to be a studio art professor at Binghamton University. While teaching at Binghamton, Wilson was commissioned to create a new monument for the center of JFK Memorial Park in Downtown Binghamton.

As an African American artist, Wilson faced many hardships due to the prejudices of the 1960s. Thus, Wilson was heavily influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and was quite fond of President Kennedy; he was quoted referring to Kennedy as a “very committed man” who created a “healthy atmosphere around the principle of involvement and commitment.” The assassination of President John F. Kennedy occurred on November 22, 1963. Though his term as president was brief, Kennedy left a lasting impact on an America that was just beginning to struggle in earnest with the poisonous legacies of racism. The president spoke eloquently about civil rights and helped put into motion legislation that would become the Civil Rights Act (signed into law the year after Kennedy’s assassination by his successor Lyndon B. Johnson). This piece is a monument dedicated both to Kennedy’s memory and to the matters of justice, fairness, and civil responsibility that were major themes of his presidency.

The Seven Seals of Silence is a three-sided monument standing ten feet tall with a granite base. Attached to the three sides are a total of twelve bronze bas-relief plaques. Particular effort was taken in the positioning and design of this monument such that the sun shines on two sides of the monument at all times, leaving one set of reliefs in darkness. Each relief includes scenes of figures that illustrate the difficulties found in our everyday life. “The Maimed and The Ignorant” presents three seated figures feeding themselves on their self-pity and ignorance. The second seal titled, “The Conformists,” has seven figures, isolated within their own compartments from one another and reality. As John F. Kennedy once said, “Conformity is the jailer of freedom and the enemy of growth.” The third seal “The Uninspired” shows three figures squeezed into a tiny space and compressed into inactivity by bulging forces from above and below. The next seal is separated into two bronze plaques titled “The Rejected.” On one, the figure is shown off-balance, in a whirlwind. The second has the figure watching the imbalance of his counterpart. “The Depraved” is meant to symbolize absolute negative involvement with three figures contorted in a powerful writhing of misdirected pleasure. Next a seal titled “The Invisible” displays the hollowed out bodies of six figures awaiting assessment on judgment day. The final seal on the monument is titled “The Dead.” It is separated into two bronze plaques; one resembles a mass of blurred forms while a body laying on the plaque below seemingly deceased.

Through these reliefs, Wilson has portrayed the consequences of seclusions from everyday life. These plaques are designed to encourage the development of one’s self, inspiring individuals to take initiative and act on their beliefs for positive forward movement. The memorial was completed in 1969; Wilson remained in Vestal until his death in 1996, at age 71.

Researched by: Maria Marcellino

The title Cono Tronco translates from Italian into “truncated cone,” referring directly to the work’s physical form. Here, a bronze cone is ruptured violently by an enormous stainless steel blade; the cone’s elaborate “insides” are made visible in the process of the rupture. Pomodoro’s work often grapples with the dichotomy of interior versus exterior, and Cono Tronco is no exception. The steel triangle that protrudes from the broken cone can be understood as the interior “soul,” as the artist calls it. A sharp formal tension emerges through the opposition of the smooth exterior geometric shapes and the work’s obscured chaotic interior. Pomodoro encourages people to interact with his sculptures—to climb on and rest against them, or to peer deep into their mysterious interiors.

Cono Tronco weighs a staggering nine thousand pounds and stands sixteen feet tall. Like most of Pomodoro’s work, it was created through the lost-wax process, an ancient technique that can produce brilliantly modern results. Pomodoro makes his lost-wax works through an elaborate multistep process. After initial designs are created on paper, he creates full-scale clay models in his studio. These large clay forms are then used to make hollow plaster molds, which are meticulously retouched after the clay is removed. Next, the plaster molds are taken to offsite to make the bronze casts. Multiple layers of wax are carefully painted onto gelatin molds made from the plaster; the wax is then encased in a mixture of plaster and silica, and subsequently baked to liquefy the wax, which melts away, leaving a void. The liquid hot bronze is then poured into the mold, replacing the “lost” wax. The encasing layer is removed after the bronze cools, and the bronze is polished and cleaned to Pomodoro’s specifications. The artist is an active participant throughout this process, engaging in every stage of creation and meticulously adjusting at every possible point.

When Cono Tronco was originally installed at Governmental Plaza in 1973, it was not in the middle of a parking lot. Upon its initial installation in 1973, the work prompted considerable confusion and misunderstanding as well as excitement. While the mayor of Binghamton at the time, Alfred J. Libous, told the local Sun Bulletin newspaper, “If you want to know the truth, it doesn’t move me.” Others reacted more positively. For example, a local IBM engineer remarked, “I think it is beautiful. I see the past, present, and future.” For his part, Pomodoro took the long view, saying: “Slowly…Very slowly…Binghamton will understand.”

Researched by: Dana Jacunski

The three female figures in William Zorach’s sculpture represent the Three Graces of Greek mythology — goddesses who traditionally symbolize charm, beauty, and fertility. Known in Greek as Charites (singular Charis), they were usually present at banquets and ceremonies to provide entertainment for guests. They were daughters of the god Zeus and the mermaid Eurynome, the latter a popular deity throughout the ancient Greek world. The Graces have long been a popular subject in Western art, appearing in works by artists such as Raphael, Peter Paul Rubens, and Sandro Botticelli (perhaps most famously in the latter’s 1482 painting Primavera).

However, Zorach’s treatment of the theme differs from traditional interpretations. The Graces are often depicted in a way that emphasizes classical ideals, such as their sweetness and femininity, and are commonly portrayed as delicate and otherworldly. In contrast, Zorach’s figures are solid and powerful, emerging together from a single mass of bronze. Standing back to back with each facing out in a different direction and united by the holding of their hands, Zorach’s figures exude strength and confidence.

“To me there is a revival of true sculptural values in the work being done today. Only time can give this art its ultimate value, but at least it is of our time and life and is of intense interest to any sculptor working today,” stated William Zorach in one of his books on sculpture. Zorach was a major modernist artist whose work appears in many major museums and collections including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Radio City Music Hall in New York. Although he was trained as a painter and printmaker, sculpture was his primary medium. Zorach rejected extreme realism in sculpture as merely decorative and lacking “human spirit.” In contrast to the casting prevalent in his day, he preferred to carve his sculptures directly, mimicking the style of ancient Greek and Egyptian stone statues. Despite Zorach being well known for his direct carving, The Three Graces happens to be one of his few cast-bronze works. Although the work was completed using the difficult lost-wax process (in which a mold is made of wax, heated, and melted to form a hollow bronze form), The Three Graces has all the forcefulness of Zorach’s better known carved pieces.

The Three Graces was a gift from the Civic Club of Binghamton to the Roberson Museum in honor of the Club’s 75th anniversary in 1973. The Civic Club believed that The Three Graces embodied the theme of their anniversary, taken from a quote by Frank Lloyd Wright: “If you wisely invest in beauty, it will remain with you all the days of your life.” Tessim Zorach, the artist’s son, played an integral role in the securing of the work for the Museum, noting that his father would have wanted his work in a public space where many could enjoy it.

Researched by: Zsuzsanna Orban

This statue of Lady Justice has been credited to the architect of the Court House, Isaac G. Perry. However, to this day the actual artist remains unknown. The 15-foot statue was brought to Binghamton and installed by the Edgar G. Freeman Company—Metal Works.

The image of Lady Justice is a common symbol found across the globe with many different adaptations. But, she always symbolizes fair and balanced justice and the promise of swift penalty. Our lady is holding two iconic symbols: the scales (representing the balance of justice) and a sword (representing the enforcement of justice). A unique feature of Broome’s Lady Justice is that she is not blindfolded, unlike virtually all other depictions of ‘blind justice.’

In 1979, Lady Justice’s sword came loose from her hand, prompting officials to rope off the south west lawn for safety. Overnight, the sword fell harmlessly to the ground. It was restored to its position atop the dome and more securely attached to Lady Justice’s hand.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia

Photographs provided by: Jillian Proscia

Roberto Bertoia (American, 1955 – )

Pegasus, 1987

Teak wood, stainless steel frame

Campus Spine, near Library Tower

Gift of the Binghamton University Class of 1985

Collection of Binghamton University

The Pegasus, a white horse with wings, is one of the most famous images from Greek mythology. According to the myth, a blow from the hooves of the Pegasus caused the fountain of inspiration to spring from Mount Helicon, a mountain peak associated with the Muses—the spirits of dance, music, literature, and memory. The Pegasus has long been a symbol of enlightenment overcoming ignorance, which is one of the reasons it was chosen as an official symbol of Binghamton University. The Pegasus is a frequent sight around campus, perhaps even more than the actual mascot of the bearcat.

One of the most visible incarnations on campus is an abstracted, outdoor wooden sculpture located right in the center of the university’s “spine.” Pegasus was the result of a contest held by the Class of 1985 to choose the class gift for Binghamton University. The contest awarded a monetary prize to an artist with the best design for an outdoor sculpture that symbolized the spirit of the school; the winner was to be hand picked by a special committee. The committee, with representatives from the Senior Class Council, alumni, faculty, professional employees, and administration, chose Cornell University professor Roberto Bertoia’s proposal for an abstracted pegasus. The work took Bertoia ten months to construct; it was dedicated in the fall of 1987.

Bertoia is known for his elegant, abstract sculptures, and wood is his primary medium. Pegasus was carved from rich teak wood, which was then bolted to a stainless steel frame and attached to a concrete base. The sculpture consists of an uneven arch that suggests a horse’s body and legs, on either side of which protrude angular, asymmetrical wings. The wings are open, as if in flight, with one horizontally orientated and the other posed vertically. The sculpture itself soars thirteen feet above its arched opening.

The sculpture has known several locations on campus. Its original location was chosen with the guidance of the Committee on the University Environment to be both aesthetically pleasing and environmentally unobtrusive. In 2012, Pegasus was moved to its current, central location in front of the Library Tower as part of an extensive reconfiguration to the campus’s main walkway. Its new location carefully places it at the intersection of two sightlines, one running north-south from the Library Tower to the Science buildings, and the other running east-west from the Student Union to Academic Building A. In its new location, Pegasus has become a place where students congregate, sitting beneath its arch. While a relatively new addition to campus, Pegasus has become more than just another incarnation of the campus symbol; rather, it is a true fixture, a work of art that students can “finally be proud of,” according to the student run newspaper Pipe Dream.

Researched by: Allison Drexler

Nathaniel Kaz, (American NYC, 1917-2010)

Wisdom’s Triumph, 1960

Bronze, stainless steel rods

Binghamton University’s Fine Arts Building

State University of New York at Binghamton

Nathaniel Kaz was born in NYC; however, his family moved to Detroit when he was still an infant. It was in Detroit that he began practicing art and quickly became a recognized child prodigy at the age of 9. With his self-portrait, he took first prize at the Annual Michigan Art Show, defeating professional adults. At the age of 13, Kaz moved out on his own and studied art at Cooper Union under the direction of William Zorach and Aaron Ben-Schmuel. At 14, he worked in NYC reconstructing statues as a part of WPIA creative arts projects. By the age of 29, he had been an art instructor for 14 years. He went on to win first prize in the 1955 United Nations contest to create a 60 foot sculpture to be erected in front of the U.N General Assembly building. His work is permanently on display in the Metropolitan Museum, the Whitney Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum.

In 1959, Nathaniel Kaz was commissioned to create a dignified symbol for the Binghamton University Campus. The Pegasus was his first work commissioned by a college. During its creation the piece was titled “Wisdom’s Triumph”. The winged horse is a symbol of enlightenment and overcoming the powers of ignorance. The Pegasus was depicted in a state of agitation to also symbolize the inner struggle to ascend with the muse.

The artwork was dedicated on June 10th, 1960 and attached to the western façade of the Fine Arts Building.

Researched by: Emily Lacey & Sara Lacey

Donald Walford (American, born 1945)

The Object, 1967

Binghamton University, Dickinson Community

Eco-Safe Materials

Gift of the artist

Owned by Binghamton University

From the moment of its initial installation in Dickinson College (as it was known then), Don Walford’s The Object has remained a beloved symbol for the entire student community of Binghamton University. Much of The Object’s long lasting appeal lies in its ability to engage the viewer on both cognitive and emotional levels: the abstractness of the work encourages analytic inspection, while its shape encourages climbing and sitting.

The Object was completed in June 1967 by Donald Walford, a Binghamton University student, as the final project for his Bachelor of Fine Arts. Walford’s first title for it was Construction No. 3, a name reflecting the sculpture’s relationship to the art movement Minimalism, which emerged in the mid-1960s. Minimalist artists often used such plainspoken, engineering-like titles for their works. Large scale, use of repeated, basic geometric forms, and direct insertion into the environment are all features of Minimalism present in The Object. The linkage between The Object and its environment is particularly important; even in present day it is a popular spot for students to meet up, study, or chat.

When The Object was formally acquired by the university in the fall of 1967, it was renamed Collegiate Structure. This renaming suggests university administrators might have aimed to associate the work with the pedagogical mission of the university. In such a reading, the interlocking beams of the work provide support to one another in order to buttress the entirety of the structure, similar to how the interdisciplinary environment of Binghamton University aims to provide a multifaceted education. In 1974, when Dickinson College was renamed Dickinson Community, the piece was renamed one final time, and given the title The Object, which it holds today.

Due to weathering, Walford’s original structure comprised of discarded wooden railroad ties decayed over time. In 2009, the original wooden structure of The Object was demolished and recast in order to make the sculpture more resistant to the elements. Walford has stayed in contact with the university, and oversaw the reconstruction of his artwork in 2009. He was also present at Binghamton University in 2013, when the sculpture was relocated to its current location, between Rafuse and Digman Halls, as part of Dickinson Community’s move to a new set of buildings. Regardless of its location on campus, The Object seems to retain its magnetic qualities. The sleek black set of bars invites one to sit for a while, alone or with others, and ruminate on the intersectionality that the piece and the campus embody.

Researched by: Daniel Bontempi

Giuseppe Moretti

(Italian, born Sienna, Italy, 1857—1935, active in the United States 1888–1935)

Workers’ Memorial, 1920

Granite and Bronze

Main Street, near Endicott Police Station

Donated by George F. Johnson, dedicated on September6, 1920

Collection of the Village of Endicott

At noon on a rainy day in September 1920, the Workers’ Memorial was dedicated in Endicott Veterans Memorial Park. The memorial commemorated the contribution of Endicott-Johnson Company workers’ during World War I. The workers’ efforts had been famously substantial: E-J factories supplied every military boot for the United States army during the war, while the workers themselves raised over five million dollars toward the war effort.

At the dedication ceremony, Endicott-Johnson president George F. Johnson, who had commissioned the memorial, said, “…unique indeed this shaft does honor to a people rarely honored in this way: the plain worker, the average citizen, the backbone of the Nation.” Johnson might have added “immigrant” to his list of honorees, as over twenty countries of the world were represented at the unveiling of the monument. Thousands of workers and community members gathered in song and prayer for the unveiling, the highlight of which was a “twenty-one bomb salute” punctuated by twenty female E-J workers, dressed in costumes specific to their home countries, pulling away twenty ropes tied to the flags to reveal the thirty foot monument beneath.

Aiming to symbolize the simplicity, dignity, and sacrifice of the Endicott Johnson workers, the memorial commemorates both the 1,710 employees deployed in active duty and the workers who remained stateside and contributed to the war through their labor. The Italian artist Giuseppe Moretti, who had relocated to Pittsburgh, carefully sculpted the monument, which faithfully reproduced sketches that were drawn up for a design apparently created by Johnson himself.

The core of the monument consists of fine granite hand selected by Morretti. Four octagonal platforms makeup the monument’s base on which two bronze sxulptures of factory workers are seated, embracing a tablet adorned with a wreath of oak and laurel leaves. Wearing factory uniforms, the figures signify the male and female workers who remained at home to make combat boots and help raise funds for the war. The tablet the two figures hold expresses Johnson’s own recognition and gratitude for these workers’ patriotic dedication. Above the two seated figures are eight bronze tablets listing the individual names of the 1, 710 workers who served in active duty, a number of whom, as Johnson put it, “For Our Tomorrow … Gave Their Today.”

The upper section of the monument honors those in active duty. Four life-size bronze figures represent four branches of the military, each dressed in uniform. Moretti’s attention to detail adds the realism of the figures: the aviator holds a propeller and field glasses, the sailor an anchor with chains, the infantryman a rifle, and the marine a rifle and sword.

Surmounting the monument is a Red Cross nurse, which Moretti attempted three times before obtaining satisfactory results. An unrolled, ready-to-use bandage delicately weaves through her fingertips as she patiently waits to bandage both the physical and psychological traumas of war. This figure serves not only as an image of wartime service but also as an emblem of the empathetic, benevolent, and democratic character of The Endicott-Johnson Company itself (promoted locally as “The Valley of Opportunity”). The nurse’s expression of maternal affection and nurturing metaphorically corresponds to the “Father-like” paternalistic altruism that “George F.,” as he was known, aimed to foster in the making of what he called his “Happy Endicott-Johnson Family”—most famously in the “Square Deal,” the unique arrangement in which Johnson provided housing, recreation, and other needs in return for almost total devotion from his employees. Indeed, like the elaborate dedication ceremony itself, the Workers’ Memorial served to bolster Johnson’s strategically produced image of his company as a “happy family.”

Researched by: Sara Dreimiller

Edward Haugevik (American, born 1951) and Linda Spirit (born 1951),

Quatrain, 1986

Stainless steel

SUNY-Broome, In between Business and Wales buildings

Commissioned by SUNY Broome Community College to commemorate its fortieth anniversary.

“Quatrain” literally means a kind of rhymed verse consisting of four lines. Much like a poem whose lines lock together to form a whole, the smooth welds of the sculpture suggests four separate but organically united parts. Further, the zigzag form of the work corresponds to the most traditional and common of quatrain rhyming schemes, that of “ABAB” (in which the last words of both the first and third lines and the second and fourth lines rhyme).

The sculpture is made of hollow stainless steel; stainless steel is highly functional for public sculpture, given its durability. The steel here was forged and then polished with a grinder, endowing the sculpture’s steel a smooth surface with brushed patterning. As the patterning catches the sunlight, it reflects and refracts it, giving the work a sense of motion. A similar approach to brushed stainless steel was employed by the famous modernist sculptor David Smith in the 1960s and the kinetic sculptor George Ricky beginning in the 1970s.

Quatrain was a collaboration between artists Edward Haugevik and Linda Spirit, who both worked with steel throughout their careers. The commission for this piece arose when a trustee of SUNY Broome saw a solo exhibition of Haugevik’s work at a gallery in New York.

With Quatrain, the sculptors created a work appropriate to a collegiate setting: the structure stretches toward the sky, much as the college offers a place for students to fulfill their potential for new heights of achievement. The work’s base and joints were deliberately de-emphasized in order to give the sculpture a sense of growing directly out of the earth, akin to the organic process of education. The upper end, which points toward the sky, offers a strong image of hope.

Researched by: HanXiao Bao

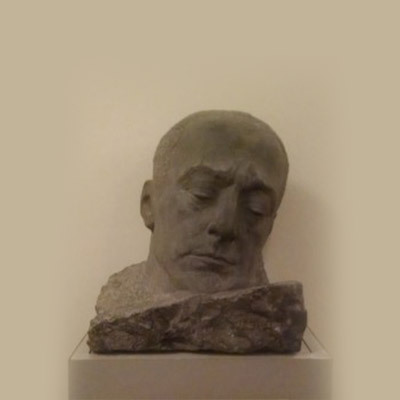

Genevieve Karr Hamlin (American, New York, NY 1896—1989 Harpursville, NY)

The High Place #62, 1984

Vermont marble

District Office Reception Area at the Harpursville Central School

Harpursville Central School

The High Place #62 was a gift from artist Genevieve Karr Hamlin to the Harpursville Central School District. Installed in an outdoor garden area, it was later vandalized. The head was stolen and was never recovered. The damaged piece has since been moved to a public area indoors. Vandals, the weather, and inadequate maintenance are constant threats to outdoor public sculpture. Fortunately, most of Karr Hamlin’s public work is displayed indoors.

The Broome County area is home to many of her works, including her bluestone bust of renowned violinist Jasha Heifetz in the Forum Theatre in Binghamton. Her life-sized, carved wooden sculpture, Iris Woman Cherry, is on permanent display in the Broome County Arts Council’s gallery space.

Both pieces were included in a 2008 retrospective at the Roberson Museum and Science Center. The show Genevieve Karr Hamlin Sculptures featured hundreds of her sculptures, bas reliefs, and carvings loaned by family, friends, and by public and private collectors.

Karr Hamlin was born in 1896 to Alfred Dwight Foster Hamlin and Minnie Florence Marston, a well known New York family. She studied art at Vassar College and continued her studies in Paris and New York City where she kept her studio until 1943. She became extremely interested in the continuation of art. At the grand opening of the Oneonta Community Center, of which she was one of the founders, she said, “America doesn’t have a national art, to have one; we must have art centers in every community in the nation.” She spent the last 45 years of her life in Harpursville, NY, teaching classes at Hartwick College and at the formerly named Roberson Center for Arts and Sciences. Karr Hamlin founded many arts centers and galleries in her spare time until her death at age 93 in 1989.

Researched by: Jillian Proscia